Black History Committee

African American Heritage

The Black History Committee of the Hays County Historical Commission coordinated the “2022 Juneteenth Essay Contest”. With a vision of promoting critical thinking, research, written communication, and verbal engagement, the essay contest was intended to motivate students to explore their city, county, state, and country. Guidelines instructed students entering the contest to write an essay that expressed their perspective of the theme. The theme of the essay contest for 2022: Why is the Celebration of Juneteenth Important in the History of Texas? The 2022 Juneteenth Essay Contest was open to 6th through 12th grade students in Hays County, Texas.

Stephanie Murray, Buda Tx

High School Division Winner

Click to read her essay! (PDF)

Nevaeh Veals. Kyle Tx

Middle School Division Winner

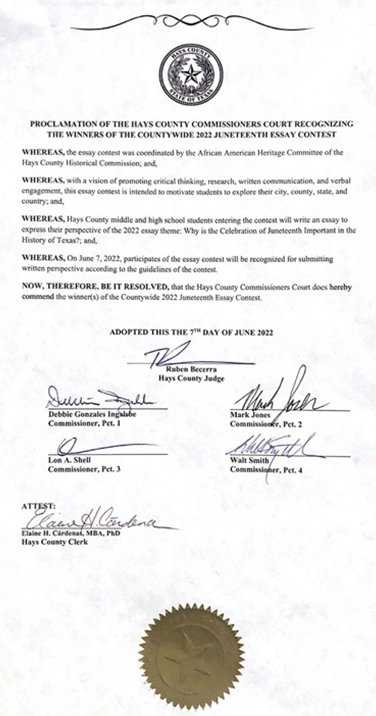

Hays County Commissioners’ Court Proclamation

Hays Commissioners’ Court Recognition

Middle School Winner – Nevaeh Veals, C. Moore (Nevaeh’s parent),

County Judge, County Commissioners, and Historical Commission Members

shown in picture

Middle School Winner – Nevaeh Veals, Commissioner Mark Jones, Crystal Moore, Nevaeh’s Mother

High School Winner - Stephanie Murray, Commissioner Mark Jones, Vanessa Westbrook, AAH Chair, Tx Representative Erin Zwiener

Announcing the 2022 Juneteenth Essay Contest

Celebrating the first anniversary of the federal holiday "Juneteenth", the Black History Committee of the Hays County Historical Commission is sponsoring an essay contest. This essay contest is open for 6th - 12th grade students in Hays County. See description, guidelines, and rules for essay contest. Winners will be announced the first week of June.

Click here for more information!

OLLIE WILBURN (HARGIS) GILES

(1933-2021)

(Based on HCHC Oral History Committee interviews with Ollie Giles and her daughter, Brenda Bell)

Ollie Wilburn (Hargis) Giles came from a line of forceful women who used the power of their personality and their eloquence to get their point across. Born in 1933, during the Great Depression, Ollie would achieve legendary status in San Marcos. An effervescent energetic woman, Ollie never shied away from voicing her opinions and championing African-American causes. When she appeared at Commissioners Court, they all sat up and paid attention. She quoted one commissioner as saying, “Oh, here comes Ollie Giles, we’re for it now!”

Ollie’s parents were L.C. Hargis and Enola Hollins, (daughter of George Mose and Etta Lee Hollins). Ollie was living with her grandparents in 1940. George Mose Hollins drove delivery trucks for the Southern Grocery Store in San Marcos while his wife, Etta Lee, ran a restaurant and a laundry. Ollie’s father, L.C., was lodging with family members in Austin, employed as a cook in a café. Her mother, Enola, worked as a housemaid in a private home in Austin. Her parents soon divorced, with L.C. moving to Michigan. Her mother and her new husband left for California, taking Ollie with them. After several

years, they returned to San Marcos.

Ollie Hargis had three husbands. The first was Frederick Marcellus Giles with whom she had five surviving children. She loved him, but grew tired of being constantly “barefoot and pregnant,” so they divorced. Her second husband was Roger Louis Bell, Ph.D.,“…a professor in New York at a college, a musician. He would play with Count Basie and (Louis) Armstrong.” Ollie and Dr. Bellhad twins, Brenda Ann and Linda Ann (Bell) Garza, born on November 10, 1963, in Seguin, Guadalupe County, Texas.

Ollie’s second marriage was falling apart by the time Brenda and her twin sister were born. She considered Dr. Bell too pretentious, constantly reminding her she was Doctor Bell’s wife and to behave accordingly. After the divorce, Ollie married Nathaniel Pleasant whom she would also divorce. She decided to revert to the married name of her first and best-loved husband, Fred Giles. She then began to pursue a career, finally becoming the accountant at the San Marcos Baptist Academy for 23 years.

History was Ollie Giles’ passion, leading to a significant discovery in the early 1990s. Ollie remembers her grandmother telling stories of a small piece of ground known as the Kyle Slave Cemetery, adjacent to Kyle Cemetery on Old Stagecoach Road, south of Kyle. She learned more from Augustus Kyle (1915-1987), a connection by marriage, of the place where his ancestors lay buried. He couldn’t remember where and was too sick to help much. Undeterred, Ollie and two relatives, Mary Ann and Catherine Fuller-Ligon searched until “…we finally found it, we had to crawl under the fence from the Kyle Community Cemetery.”1

Once Ollie Giles and her cousins finally located the hidden cemetery, it was not long before things began to happen. By 1993, the Hays County Historical Commission was involved, starting a cemetery-restoration program and initiating a perpetual trust fund to help maintain small forgotten cemeteries in the county. On Saturday 4 December, 1993, it was obvious restoring the old slave cemetery had become a community-wide project. About 100 volunteers rolled up their sleeves and got to work clearing weeds, brush, and trees. Hays County Commissioners provided the equipment. Members of the Hill Country Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Hays County Historical Commission, the Boy Scouts of America, and students from Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State University) provided hours of labor.

The Southwest Texas State University chapter of the NAACP received a grant to build an iron fence and gate. Hays County Historical Commission took on the task of restoring the headstones. Winton Porterfield, the Commission’s cemetery-committee chairman, was the driving force behind the project which resulted in a Certified Local Government grant from the National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Lila Knight, chairman of the Hays County Historical Commission at the time of discovery, believed it to be “one of Hays County’s most important sites.”2 The consequent restoration efforts brought together a diverse group of volunteers and was responsible for the formation of Hays County Historical Commission’s “Adopt-A-Cemetery” program, and of the Hays County Commissioners Court voting to set aside money to maintain the grounds of certain cemeteries.3

In 2007, Ollie Giles petitioned the Commissioners’ Court for a change of name from the Old Slave Cemetery to the Kyle Pioneer Family Cemetery. This was officially entered in the Hays County records. It has since been designated a Historic Texas Cemetery, followed by the award of a historical marker. Unfortunately, Ollie Giles was not well enough to attend the very moving dedication ceremony in 2019.

Ollie Giles leaves behind a significant legacy. She was a true champion of the African American community in Hays County. Her determination, eloquence, intelligence, and appreciation of history shone through. Her bubbly personality and sense of humor are evident in the interview conducted by the Hays County Historical Commission which can be viewed here.

©2021 J.Marie Bassett

1) Hillside Scene Magazine, Southwest Texas State University, San Marcos - February 1994.

2) Austin American-Statesman - June 29, 1994.

3) Ibid - May 4, 1993.

Did you know that…

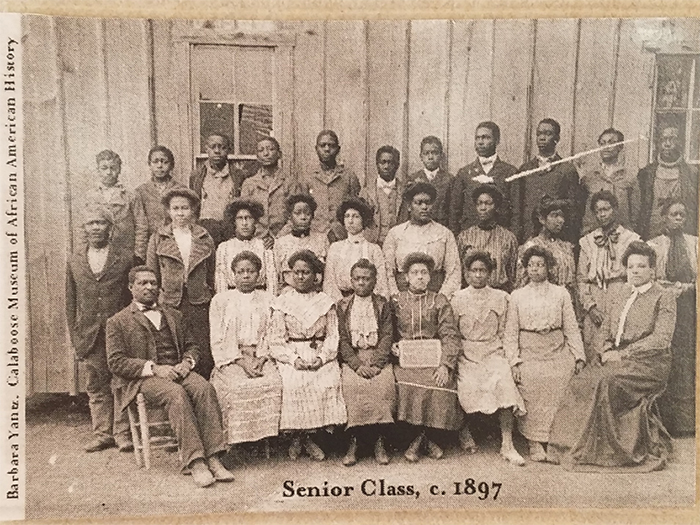

Texas’s Constitutional Convention of 1866 proposed a system of public education which included separate schools for African American children. The Texas Constitution of 1876, Article 7 Section 1, stated “... it shall be the duty the Legislature of the State to establish and make suitable provision for the support and maintenance of an efficient system of public free schools.” This led to the formation of a Negro School District with four public schools in Hays County — Antioch, Pleasant Hill, San Marcos, and Berry Durham. Property (four acres) was purchased on South Fredericksburg Street in San Marcos from Major Ed Burleson Jr. The San Marcos school, known as the Negro School, opened on January 13, 1877.

Circa 1897, when the photograph was taken, the principal was Professor L.D. Simmons, assisted by M. A. Dobson and Kittie Smith. In 1918, due to the growth of the African American population, the school building was moved to a 7.3-acre site at Endicott and Comal Streets, and a new larger room was added. One of the longest serving teachers and former student was Ola Lee Coleman who retired after 37 years in 1952, two years before integration became law. When a name change was proposed in 1961, Ola Lee Coleman School was one of the suggestions. However, the school board selected the name Paul Lawrence Dunbar (1872-1906), African American author from Dayton, Ohio.

After integration was complete in the 1960s, Dunbar School closed.

Pictures of the Past (coming soon)